A statue of the legendary Irish guitarist Rory Gallagher has been unveiled in Belfast city centre – check it out below.

The rock and blues musician is often cited by other guitarists, including Eric Clapton, The Edge and Brian May, as one of the greatest players of all time, both for his solo work and for his time leading the band Taste in the 1960s.

The County Donegal native played in Belfast many times over his three-decade career and now he has been immortalised with a bronze statue outside the city’s Ulster Hall on Bedford Street, with a ceremony being held to mark its unveiling.

“He’s finally here!” announced the venue on X on Saturday (January 4). “Today we’re celebrating the legacy of Rory Gallagher with the unveiling of a new statue of the legendary guitarist outside Ulster Hall.”

Members of Gallagher’s family were joined by fans and local signatories for the unveiling, with the Lord Mayor of Belfast Mickey Murray commending Gallagher’s authenticity and talent.

The statue itself was created by Anto Brennan, Jessica Checkley and David O’Brien of Bronze Art Ireland, with the design being inspired by a photograph that first featured on the cover of a January 1972 issue of Melody Maker magazine.

Barry McGivern of the Rory Gallagher Statue Project Trust told the BBC that he felt it was a “fitting tribute” to the musician.

Speaking about his close connections to the city, he added: “In Belfast, with Taste, he would have played with John Wilson and Richard McCracken [from Northern Ireland], they were a power trio and that helped to give him his wings, and the people of Belfast allowed him to flourish.”

“When he played the Maritime in Belfast, there were queues the whole way round the block to the New Vic. Rory also lived in a guest house in Cromwell Road off Botanic Avenue. He would have played various venues in Belfast as well as the Maritime, including the Ulster Hall, Queen’s University, the Grosvenor Hall, Sammy Houston’s Jazz club, Romano’s, and the Pound.”

Gallagher has regularly been voted as one of the greatest rock guitarists of all time, and he sold over 30 million records worldwide. His most celebrated albums include his self-titled solo debut in 1971, ‘Deuce’ later the same year and the live albums ‘Live! In Europe’ (1972) and ‘Irish Tour ‘74’ (1974).

Ulster Hall will be screening a documentary film inspired by the latter album tonight (January 4) to mark the occasion.

Gallagher had a number of health problems, before being admitted to hospital in London in 1995 for liver failure. After contracting hospital superbug MRSA, he passed away later that year at the age of 47.

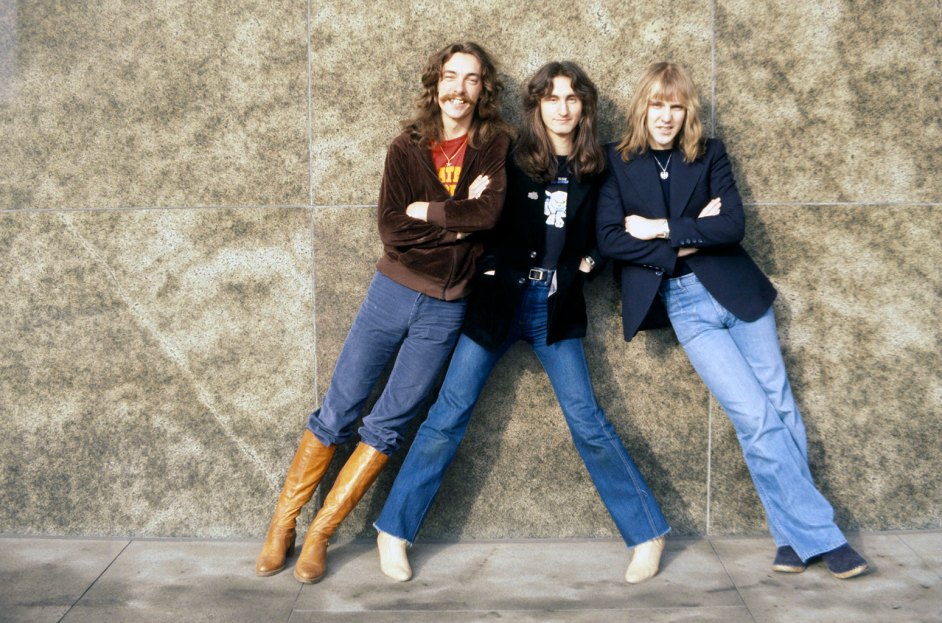

The surviving members of Canadian progressive rock outfit Rush have reflected on their final tour, sharing their regrets that the tour didn’t extend to the likes of the U.K. and Europe.

Close to ten years on from their final run of shows, Rush bassist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson spoke to Classic Rock magazine about the group’s last gigs, apologizing to the British and European fans who didn’t get a chance to see them perform live.

“I’d pushed really hard to get more gigs so that we could do those extra shows and I was unsuccessful,” Lee said of the band’s R40 Live Tour. “I really felt like I let our British and European fans down. It felt to me incorrect that we didn’t do it, but Neil [Peart] was adamant that he would only do thirty shows and that was it.

“That to him was a huge compromise because he didn’t want to do any shows. He didn’t want to do one show.”

Rush’s R40 Live Tour kicked off in Tulsa, OK in May 2015, and featured a total of 35 shows across the U.S. and the band’s native Canada, ending in August of that year. Ultimately, while Rush’s dedicated fanbase called out for more dates to be added, these would become the final performances from the veteran band. Despite releasing their final album, Clockwork Angels, in 2012, Rush’s dissolution wasn’t confirmed until the death of longtime drummer Neil Peart in January 2020.

While Lee would detail the band’s final tour in his 2023 memoir, My Effin’ Life, he admitted to being very cautious in regard to how he discussing Peart’s death, but strived to be as candid as he could so as to give Rush’s audience the closure they wanted about the band’s end.

“I just kind of felt I owed an explanation to them, the audience,” Lee explained. “It’s part of why I went into the detail I did about Neil’s passing in the book, was to let fans in on what went down. That it wasn’t a straight line.

“This is how complicated the whole world of Rush became since August 1 of 2015 until January 7th of 2020 when Neil passed. Those were very unusual, complicated, emotional times. Fans invested their whole being into our band and I thought they deserved a somewhat straight answer about what happened and how their favourite band came to end.”

Lifeson also expressed his disappointment about Rush being unable to tour some of their favourite markets as part of their final run, noting that while Peart’s scheduling demands and health issues made further shows impossible, an additional “dozen or so” dates may have made the surviving members “a bit more accepting”.

“There was a point where I think Neil was open to maybe extending the run and adding in a few more shows, but then he got this painful infection in one of his feet,” Lifeson added. “I mean, he could barely walk to the stage at one point. They got him a golf cart to drive him to the stage. And he played a three-hour show, at the intensity he played every single show.

“That was amazing, but I think that was the point where he decided that the tour was only going to go on until that final show in LA.”

Having formed in Toronto in 1968 by Lee, Lifeson, and original members John Rutsey and Jeff Jones, Rush began to find widespread fame throughout the ’70s, with Peart replacing Rutsey following the recording of their 1974 self-titled debut.

While much of Rush’s touring was confined to the U.S. and Canada, the U.K. was their next most popular market, with European countries such as Germany and the Netherlands following behind. Curiously, Rush rarely ventured beyond these territories, with countries such as Australia never hosting the band on their shores.