Three years ago, no one would have predicted that a ragtag group of NFL players would put out an album of music that didn’t just break into the Billboard charts but actually sounded good. Yet The Philly Specials — as Philadelphia Eagles offensive linemen Jason Kelce, Lane Johnson and Jordan Mailata called themselves — did just that and much more. Over the course of three holiday albums, they’ve not only become unlikely chart stars, attracting luminaries from the actual pop music world to collaborate, but they’ve raised astounding sums for charity with each release.

And in an unprecedented feat of philanthropic outreach, the proceeds benefited Operation Snowball, which delivered a gift to every student and teacher in the School District of Philadelphia (for a total of 1.1 million items) in partnership with the Fund for the School District of Philadelphia, with the players making in-person visits to spread holiday cheer.

Like its two LP predecessors, A Philly Special Christmas features the unlikely vocal talents of Kelce (now retired from his legendary run as the Eagles’ cente,r but busy as ever hosting the New Heights podcast with his brother, Travis Kelce; ESPN’s Monday Night Countdown; and, now, the network’s new They Call It Late Night With Jason Kelce), Johnson and Mailata, along with high-profile musical guests (Stevie Nicks, Boyz II Men).

But the album wouldn’t have become a hit without two key behind-the-scenes forces: Connor Barwin – a longtime friend of Kelce’s, who is himself a former Eagle (and also now the organization’s head of football development and strategy) – and Charlie Hall, drummer for alt-rock arena-fillers The War on Drugs and the Philly Specials’ producer and musical director.

Barwin and Hall spoke to Billboard as they recovered from the whirlwind release of A Philly Special Christmas and Operation Snowball about what football players and musicians can learn from each other, watching Jason Kelce and Stevie Nicks duet, and discovering Travis Kelce’s vocal talents.

Tell me a bit about your individual roles in getting the album together.

Connor Barwin: It started with being good friends with Jason, Lane and Jordan. I played with Jason from college [at University of Cincinnati] till Phill,; played with Lane in Philly for a long time — and then working for the team, obviously got to know Jordan really well. I heard Jason throw out this idea of making a Christmas record, and I knew all these guys were very talented musically.

I’m someone who really appreciates and loves music and had gotten to know quite a lot of people in the music industry through my [Make The World Better Foundation] that I started when I came to Philly. And one of the many wonderful benefit shows I’ve thrown was with Charlie and The War on Drugs. Jason knows Charlie as well – he’s one of the best musicians, he’s an Eagles fan, he’s local – so I immediately thought, “This is who we should call.”

We all got together and Charlie started asking the right questions: What songs are important to you? How do you think about Christmas music? We sort of left that meeting all very much committed to taking it seriously. My role from then on has been trying to keep it all together; there’s a lot of busy people, a lot of different stakeholders, so making sure we’re finding time to do this the right way, where it doesn’t intersect with their main career — which is playing football for the Eagles — but finding a balance, because this is very fun and fulfilling for them.

Charlie Hall: I don’t think we had any idea when we started doing this what sort of shape or scope it would have. But from that first meeting, just seeing the way the guys were passing the guitar around, it was like wow, these guys are deeply connected, they’re doing this thing at the highest level in their “real” jobs but they also approach music with that same mindset of “we want to make this great.” And they did!

When you set out to make this third record, did you have in mind big goals in terms of people you wanted to get on it or songs that you wanted to take on?

Barwin: With how old we all are, and being in Philadelphia, it made sense, like — if we could ever get Boyz II Men on the record, that would be incredible. But at the end of the day, I never really had any goals other than making something we were proud of, having fun and raising money.

Who’s harder to convince to participate: high-profile musicians or football players?

Hall: It’s scary singing into a microphone, hearing yourself that closely and in headphones… There’s a lot of the guys’ friends [on the team] that can sing, but I would probably argue that it’s a little harder to get some of the players.

Barwin: Yeah, I agree. But it’s also been really fun watching these guys in the studio with professional musicians and seeing how they’re inspiring each other. As a former athlete that still works in the NFL, it’s really cool to just show everyone that these guys, who are some of the best football players in the world, are brave enough to try something that they’re not completely comfortable with. It’s an inspiring thing for a lot of people, whether they’re athletes or not, to see: that if you or the world is putting you in this one place, you can try something else. It’s cool for kids to see that…

Hall: And for their teammates to see that, for the musicians to see it. To see these guys out of their element just going for it and having the confidence to try and get better… I learned so much from every single person that came through that door, musically, interpersonally, professionally.

Jeff Stoutland, aka Stout — the Eagles’ legendary run-game coordinator and offensive line coach — has a humorous feature on this album’s cover of “It’s Christmas Don’t Be Late,” better known as The Chipmunk Song. How did you get him involved?

Barwin: Stout is known as one of the most hardcore, best coaches in the world, and it’s no surprise to me that he understands how fun and important something like this is. But the Chipmunks thing was a Charlie/Jason idea that came out of the studio. You really love that song, and Jason thought, “You know, Stout would be perfect,” and he was game for it. People know how great of a coach he is, but he really looks at these guys like family, and he’s so proud of them to be doing something outside of football.

Hall: I think Stout gets a kick out of it – and [he likes] showing the guys that yeah, doing something off the field has impact.

The big reveal of Stevie Nicks on the record, duetting with Jason on Ron Sexsmith’s “Maybe This Christmas,” was huge. How did that happen, and what was it like seeing her and Jason working together?

Barwin: I mean, just seeing her was amazing, and then seeing her with Jason was very cool, the respect they had for each other and how happy they were to be together doing this. The backstory is, you know, as the Kelce family’s rise has happened, I think there was just some admiration [on Stevie’s part] for what a wonderful family they are. And I think Stevie had met Travis at a show before, and so their teams had sort of known each other, and Charlie had this song, so we said, you know, let’s ask Stevie if she wants to do it, she would be perfect for this. And she was game right from the beginning. When she came to the studio, she was so happy to be there, and she was awesome to be around.

Hall: I think it’s fair to say that sense of humor is part of the connective tissue here. You think of Stevie as this, like, magical creature who exists on like another plane, and yes, she kind of is, but then there’s this sense of humor that was at the forefront of her and Jason’s connection.

There was a very positive fan reaction to Travis’ first Philly Specials vocal appearance last year on A Philly Special Christmas Special, on “Fairytale of Philadelphia” with Jason, and he returns here on “It’s Christmas Time (In Cleveland Heights)” with Jason and Boyz II Men. He does a full-on ‘90s-style slow jam spoken intro and sings quite nicely. Were his vocals a surprise, or is he just naturally talented at singing, too?

Hall: Totally naturally talented. And kind of approaches things head-first, just scratch- scratching away, and then bam, it’s there. It was really, really awesome to watch both years the way he approached his stuff – he’d just jump in there and literally find his way. And his and Jason’s voices, they obviously share DNA, so there’s a quality that makes them blend really well.

Barwin: So here’s a story I can tell: Charlie went out to KC to record Travis both times. And the first time, Charlie gets back and tells me, “That’s one of the most wild things I’ve ever witnessed in my life.” Because they started working on the song and in the first like 10 minutes, Travis is singing, and Charlie was like, “Oh, I don’t know if this is a good idea…” And then Travis asked to hear it back, and then asked for some feedback, Charlie gave him some feedback – and then the dude just got in there, and in like 15 minutes, found it. It went from “this might not work” to “holy s–t, this guy is in it, we gotta keep going!” It speaks to just how much of a talent and a performer he is, and why he’s such a great athlete and been so successful.

It’s been so fun to discover some of the hidden vocal talents among the Eagles, like Jordan Davis last year. Are there any other hidden gems on the team who, if you were continuing the project, you’d want to get on wax?

Barwin: I need to find that out — I know there’s a few. I’m not going to put them out there on blast right now, because then people will be begging them.

Hall: And we know who is not, and we’re not going to say that either. [Laughs.]

The Philly Specials project has just become more and more successful – why stop now?

Barwin: I think it just feels like the right time, being the third one, to end. It’s just such a special thing that happened, and I think all of us don’t want to change that and overdo it. We just want to keep it as magical as it’s been. Who knows where we’ll all be come next summer — maybe there’s a song or two, a couple more Eagles who can sing, or special guests that that we end up doing something to sort of keep this tradition going. But right now, it feels like maybe stop while we’re in a good place.

Hall: It truly has become this kind of strange, giant family that’s definitely connected for life. So who knows?

Barwin: What we were able to scale up and do this year has never been done before, and there are really big partners that want to find a way to do it in maybe other cities and with other teams, other players. So you know, who knows where this will end up. At the end of the day, there’s still such a big opportunity to continue to merge [the sports and music] worlds together for the benefit of everybody, for both athletes and musicians. We don’t quite have it figured out, but we’ve met a lot of people and know how to keep the artists and the athletes in the front position and make sure the music is at the forefront. And when you do that, you’ll make something that people connect to. Hopefully we can be helpful in facilitating more stuff like this.

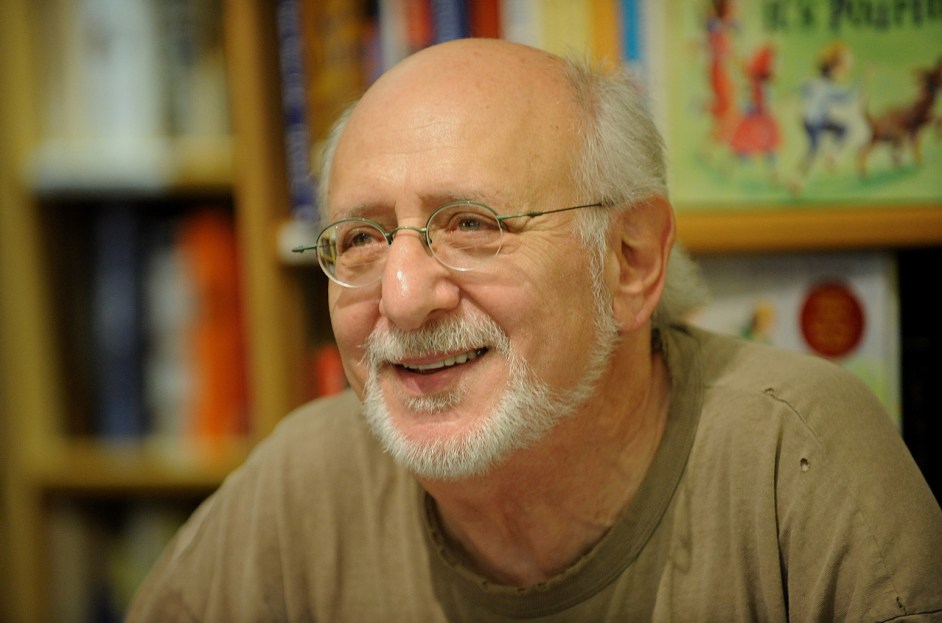

Peter Yarrow, one third of the beloved 1960s folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary has died at 86. According to the New York Times, spokesperson Ken Sunshine said the singer and anti-Vietnam War activist died at his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan following a four-year battle with bladder cancer.

With his high tenor melding seamlessly with baritone Paul Stookey and contralto Mary Travers, Yarrow and this singing partners produced some of the most beloved songs of the 1960s, taking the lead on classics “Puff the Magic Dragon,” “The Great Mandala” and “Day Is Done,” all of which he wrote or co-wrote.

Perhaps the group’s most well-known track, “Puff the Magic Dragon,” was penned by Yarrow based on a poem by fellow Cornell grad and author Leonard Lipton about a magical dragon name Puff and his human friend, child Jackie Paper, who take off on adventures in the magical land of Honalee. Fans of the 1963 song — which was later turned into a beloved 1978 animated special and two follow-up sequels — were convinced that it was larded with secret drug references, tagging it as a trojan horse ditty about smoking weed, a claim both Lipton and Yarrow repeatedly denied.

The song was one of the group’s most successful on the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at No. 2 on the tally in May 1963. Following Yarrow’s death and Travers’ passing in 2009 at age 72, Stookey, 87, is the group’s last living member.

“Our fearless dragon is tired and has entered the last chapter of his magnificent life. The world knows Peter Yarrow the iconic folk activist, but the human being behind the legend is every bit as generous, creative, passionate, playful, and wise as his lyrics suggest,” daughter Bethany Yarrow said in a statement according to the Associated Press.

Yarrow was born in Manhattan on May 31, 1938 and after starting his singing career as a student while pursuing a degree in psychology at Cornell University in the late 1950s. He moved back to the city to begin performing in New York’s burgeoning Greenwich Village folk scene after graduation. After a performance at the Newport Folk Festival, he met the event’s founder and famed music manager Albert Grossman, who shared his idea for putting together a vocal group in the vein of the Weavers, a harmony quartet from the 1940s and 50s that sang traditional folk and labor songs as well as children’s tunes and gospel; it originally featured beloved folk singer/songwriter Pete Seeger.

It was Dylan manager Grossman’s idea to put Yarrow and Travers together, with the latter later suggesting the addition of Stookey, who both had performed with on the folk scene. After signing to Warner Brothers Records, they debuted in 1962 with the song “Lemon Tree,” which peaked at No. 35 on the Hot 100. Quickly establishing their folk credentials, they followed up with the 1949 Seeger/Lee Hayes-penned protest anthem “If I Had a Hammer,” which won them two Grammy Awards in 1962 for best folk recording and best performance by a vocal group; they were also nominated for best new artist that year. They picked up two more Grammys the next year in the same categories for their cover of Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and a fifth one in 1969 (best recording for children) for the Peter, Paul and Mommy LP, which peaked at No. 12 on the album chart.

Among their string of hits on the Billboard Hot 100 were their 1969 No. 1 cover of John Denver’s “Leavin’ on a Jet Plane,” as well as the No. 9 charting “I Dig Rock and Roll Music” and the No. 21 hit “Day Is Done.” They were also well-known for their charting covers of such Dylan classics as “Blowin’ in the Wind” (No. 2, 1963) and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” (No. 9, 1963), scoring a total of five top 10 albums on the Billboard 200 chart. Two of those albums, a self-titled collection from 1962 and 1963’s In the Wind, reached No. 1. (Those albums held the top two spots simultaneously, an extremely rare feat, on Nov. 2, 1963. In the Wind jumped from No. 12 to No. 1 in its second week. Peter, Paul And Mary slipped from No. 1 to No. 2 in its 80th week.)

In keeping with the tenor of the era, the group were also notable for their strong, progressive political stance in song (“The Cruel War,” “Day Is Done”) and in practice. They participated Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington in 1963, performing Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” (and “If I Had a Hammer”) on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, helping to cement that song’s place as a civil rights anthem.

In total, the group released nine albums during their initial run before breaking up in 1970. It was around that time that Yarrow was accused of taking “immoral and indecent liberties” with a 14-year old girl, Barbara Winter, after she and her older sister came to his hotel room for an autograph and he answered the door naked and forced her to perform a sex act on herself. The singer was indicted and sentenced to one to three years in prison, and ended up serving just three months. He later apologized for the incident and was granted a presidential pardon by Jimmy Carter in January 1981, just before the late president’s final day in office.

Yarrow was also an indefatigable anti-war protester, helping to organize the anti-Vietnam National Mobilization to End the War protest in 1969 in Washington that drew nearly 500,000 fellow anti-war activists, as well as 1978’s anti-nuclear benefit show Survival Sunday at the Hollywood Bowl, which featured appearances by Jackson Browne, Graham Nash and Gil Scott-Heron, among others. In 2000, he founded Operation Respect, a non-profit that aimed to tackle the mental health effects of school bullying.

In addition to his work with the trio, Yarrow released five solo albums, scoring a No. 100 hit on the singles chart with “Don’t Ever Take Away My Freedom” in 1972 and a No. 163 debut on the Billboard 200 album chart in 1972 for his debut solo LP, Peter. Following solo ventures by all three, the trio reunited several times over the ensuing years, including for a 1972 concert to support George McGovern’s failed presidential campaign, his 1978 Survival Sunday anti-nukes show and a summer reunion tour that same year.

By 1981 they were back together for good, performing and releasing five more albums before Travers’ death.

Check out some of Yarrow’s highlights below.