As the 20th century tripped into the new millennium, dark energy rippled through the universe that Bill Callahan had dreamed into being. The music he’d spent the previous decade creating as Smog had maintained a tenuous balance of bleak beauty and wry humor. Then, for a minute there, with 1999’s revelatory Knock Knock—a breakup record and a finding-himself record that featured some of the most unburdened songwriting of his career—it seemed like maybe he’d turned a corner, tamed some demons. “For the first time in my life/I am moving away moving away moving away/From within the reach of me,” he sang on “Held,” as if the speaker’s soul was a Mylar balloon escaping the white-knuckled fist of a bitter, stunted man-child.

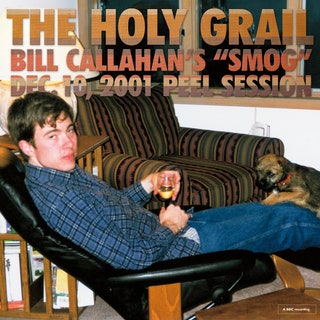

But gravity’s a hell of a drag, and with 2000’s Dongs of Sevotion and 2001’s Rain on Lens, Callahan was back down in the muck with his usual cast of characters: disappointing siblings, obsessive nihilists, ambivalent shut-ins, and, above all, unreliable men with broken moral compasses. In December 2001, wrapped in this darkness, he and his touring bandmates—drummer Jim White, violinist Jessica Billey, and guitarist Mike Saenz—stepped into the BBC’s Maida Vale studios. The set they recorded that day with John Peel, two Smog originals and two covers, has finally made its way to record, billed as The Holy Grail. Despite its tongue-in-cheek title, for the Callahan faithful, it’s a fantastic find—a snapshot of the artist and his band at their most stripped down, highlighting his music’s sinister yet generous essence. The inclusion of two covers, something of a rarity in Callahan’s repertoire—and not just any two covers; the Velvet Underground and Fleetwood Mac, of all bands—only sweetens the deal.

Critics in those years, particularly in the UK, tended to treat Callahan like an incurable pessimist; the Smog songs that Callahan chose that day certainly don’t seem meant to disabuse them of that notion. Both tracks prod ominously at the ambiguous sexual underbelly of his work, stirring up uncomfortable questions about how much we’re meant to sympathize with the songs’ grim protagonists.

“Cold Discovery,” from Dongs of Sevotion, doesn’t sound unduly severe at first. Where the album version weaves flanged guitar, piano accents, and whispering drums into a downy two-chord shuffle, the Peel version is stark and unadorned, with a hint of distortion on the twinned guitars, and brushes on the drums hissing out a funereal beat. Still, there’s something hypnotic about its rising and falling motion; the sweetness of Callahan’s baritone papers over the hints of desolation in the lyrics. He sings of warm returns and bitter leave-takings; the first stanza might conceivably be about a beloved stray cat. But he lets loose with the chorus: “I could hold a woman down on a hardwood floor,” an incongruously sing-song lilt coloring his voice. The band surges like ocean swells, reflecting shades of Swans’ or Sonic Youth’s steely dronescapes. He repeats the line, as though rubbing our faces in it. But as in most Callahan songs, there’s a twist. The violence, if that’s what it is, is reciprocal, as her teeth “gnash right through me/Looking for a soft place.” The “cold discovery” of the title is his fundamental lack: Searching for empathy and vulnerability, his lover finds none. It’s a damning self-assessment.

Next, the musicians take Rain on Lens’ Sabbath-y “Dirty Pants,” pitch it down a step or two, and make it even slower and more dirge-like. Callahan paints a bacchanal scene: “And so I dance in dirty pants/A drink in my hand/No shirt and broken tooth/Barefoot and beaming.” There’s a stomping, singing crowd, broken glass and ringing blood; whatever it is that happens next, it’s charged, again, with the threat of violence, shot through with undertones of humiliation and bedlam. Billey’s violin is wraithlike; the guitars dig into a doom-metal trudge. “God does not answer this type of prayer/No no no,” Callahan intones. It’s a menacing take on one of the most desolate songs in his catalog.

What are we to make of his cover of Fleetwood Mac’s “Beautiful Child”? Even in the Tusk original, the song’s story of an impossible love is deliberately vague. Stevie Nicks wrote the song about an affair with a married man many years her senior. The lyrics are a sort of lenticular image, flipping from her lover’s voice (“Beautiful child/Beautiful child/You are a beautiful child”) to her own meditation on desire and regret. Callahan takes ample liberties with the song’s architecture—changing the chord progression, the melody, even flipping it from major to minor—but he sings the lyrics virtually verbatim. On the one hand, it’s a gorgeous, sad rendition of Nicks’ heartbroken ballad. But knowing the kinds of figures that tend to populate Callahan’s own songs, it’s hard not to feel a sense of unease when confronted with one couplet in particular: “Your eyes say yes/But you don’t say yes.” Callahan takes Nicks’ wistful song of innocence and disillusionment and turns it several shades darker.

Having opened the EP with this forlorn, damaged lament, Callahan closes the record in the only possible way: with a prayer. Like his Fleetwood Mac cover, “Jesus” sounds little like Lou Reed’s original—new key, different chords, none of the vocal harmonies that make the Velvets’ song so plaintive. Callahan delivers the song’s repeated plea—“Help me find my proper place/Help me find my weakness/’Cause I’m falling out of grace”—just once; it’s the only time that he sings on the song, his voice low and sorrowful. Instead, over slow, ruminative guitar, nearly inaudible drums, and a single, drawn-out violin note, Callahan murmurs the name “Jesus.” He says it a dozen times, his voice falling in volume toward the end of the short, anticlimactic song. It’s a remarkable reading, and a stunning capstone to the session. It feels unusually grounded for a Bill Callahan song, at least one from that era. After the preceding portraits of inscrutable men with shadowy aims, it feels like a welcome state of grace.

Share

Share