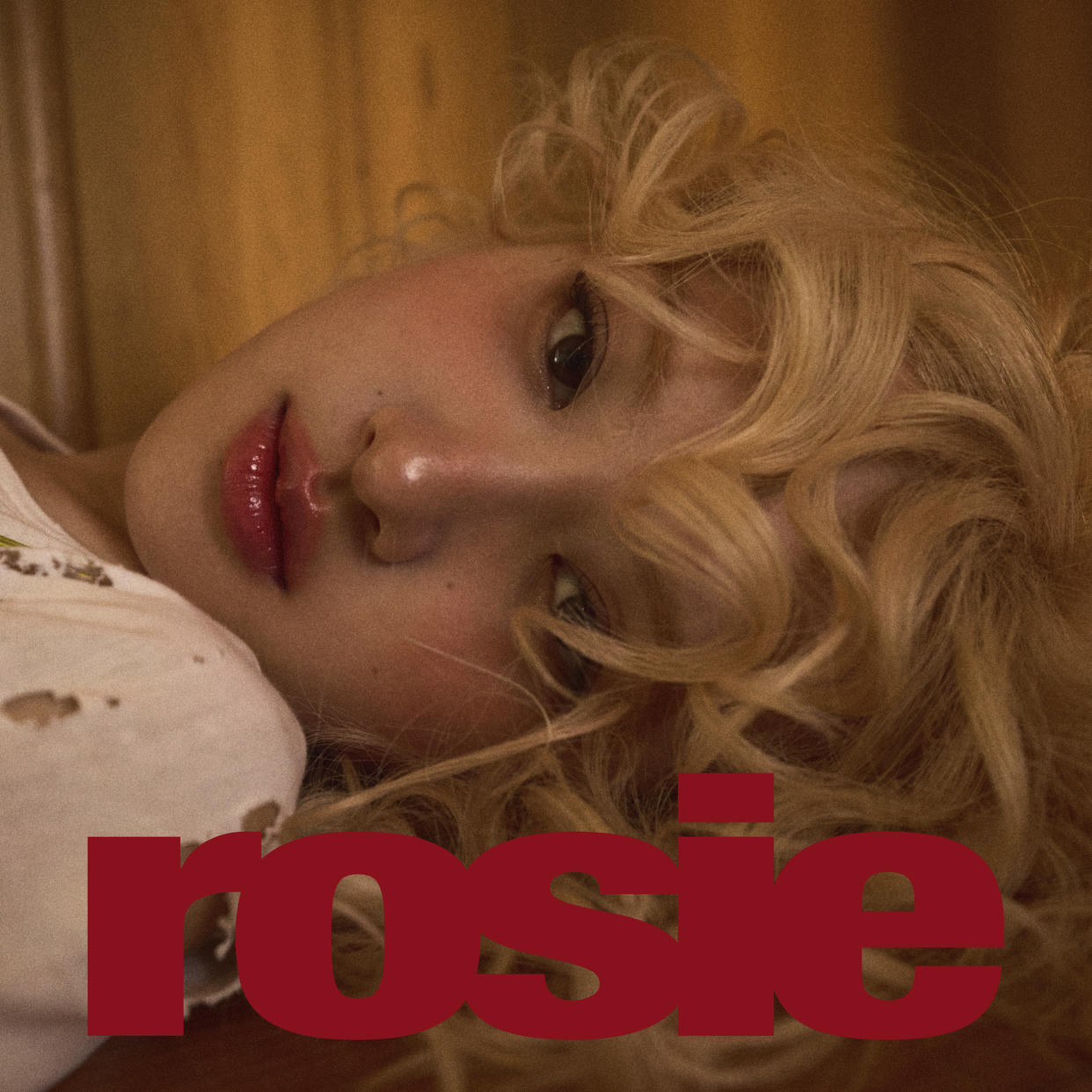

London-based lo-fi electronic musician Leo Bhanji has said that he feels successful as a songwriter when he’s able to express confusion in his work. His songs eschew causality and linear narrative for vibrant pastiches of half-revealed secrets, flickers of regret, and inner monologues. On his new EP, Shell, he deftly uses this oblique approach to relay the turmoil he feels as he falls in love, often despite his own best intentions.

By weaving together past, present, and future, Bhanji cultivates a sense of purposeful chaos. He begins the gentle guitar ballad “Hazel & Deadnettle” looking forward to a love interest’s arrival, then ruminates on a night in the past when their relationship likely ended. The song closes with a blurry, mysterious image that similarly evokes both present and past: “See your picture way after it’s gone, it’s burning.” On “Lung,” he claims that he doesn’t want to fall in love, but the glinting blips of synth betray the anticipation and intrigue of a forthcoming romance. Like light through glass, these stories, warped through the prism of time, fracture into keen observations, eager dreams, and nostalgic memories.

Shell’s opaque lyrics are made even more so by Bhanji’s loose, gravely vocals. His words melt together and bleed into the watery production. A handful of phrases in each song function like auditory Rorschachs, jumping out of the soup of imagery to come into sudden focus. The effect can add an interesting texture and meta-narrative: On “The Invisibles,” the phrase “I’ll end up falling in love again” lingers, imbuing the song with a poignant mix of sadness and hope. But when a prominent phrase is even a little bit mundane, it can make the whole song feel platitudinal. On “Dance W U,” Bhanji repeats the phrase “You know I’ll leave any party for you” a handful of times. It’s an uninspiring promise that rings hollow.

Rather than producing his own music as he often has in the past, Bhanji worked with producer Felix Joseph (AJ Tracey, Jorja Smith) on Shell. Bhanji credits Joseph with keeping his music more focused. The songs, though sparse and streamlined, don’t quite achieve the propulsiveness of Bhanji’s best work. On “Damaged,” from his 2021 EP Birth Videos, a gossamer choral sample collided with an unrelenting beat that then buoyed a sped-up and distorted vocal outro. Poetic ruminations were punctuated with candid group-chat wisdom: “I sleep with my eyes open, dream the black around my lids” was followed by, “Everyone’s heart freaks me out.”

Comparatively, the songwriting on Shell is less astute and deliberate, the meandering observations less rich in insight. And while the delicate wash of synth and guitar work is lovely, it feels more subdued and less exploratory. Bhanji’s music is most compelling when he relays dispatches from a mind that’s processing, reminiscing, yearning, and anticipating all at once, without losing sight of how he feels about it. There’s a real vulnerability in allowing you to witness the world alongside him: to sense its little pleasures and beguiling contradictions in real time, together.

Share

Share