Though she has spent nearly four decades as an icon of nonchalant alt-rock cool, Kim Deal is no stranger to the big gesture. The indie-rock standard she penned as bassist of Pixies is called “Gigantic,” after all. When she struck out on her own with the Breeders, her hit, “Cannonball,” was about diving into hell and making the hugest possible splash. But Deal has never taken such unexpected swings as she does on Nobody Loves You More, her first proper solo album since becoming a fixture in the story of indie in 1986. Ninety seconds into the opening track, a full-blown brass section bursts in, announcing a different side of Deal, and unlocking the baroque-pop grandeur hidden in the heart of a slack-rock god.

Deal’s voice is a sly smile, sweet and tough, like candy and cigarettes. Holding rock’s loud-quiet surges at the impressionistic simmer of a punk Rothko, she remains an avatar for the power in being oneself, which often requires acceptance of the unknown, the possibility of the hard fall. She has accordingly spent recent interviews stating that her favorite part of art is failure. “Maybe not the failure itself,” Deal clarified, “but the stories that come from it.” She said elsewhere: “There’s something really sweet and endearing about somebody who got their ass kicked. They were out there trying.” The blistering blood harmonies of the Breeders—which Deal still helms with her twin sister Kelley—have by now traveled from the biker bars of Dayton, Ohio, to the arenas of both the In Utero and Guts tours. The chronicles of Deal’s “please-no-chops” entry into Pixies, gigging in her 1980s secretary clothes, are indie-rock folk tales. But risk has always been the subtext.

At times the lavish precision of Nobody Loves You More imagines Deal on an island masterminding her own meticulous Pet Sounds. Though she’s been Breeders’ primary songwriter for over three decades—and has likened her 1995 side-project the Amps, a lo-fi rock band, to a solo record—Nobody Loves You More is the first time she’s followed every sonic impulse and fully owned them, even as she’s joined by 20 other musicians. Deal strums a ukulele on the majestic orchestral ballad “Summerland.” She delivers a loose rap on the industrial “Big Ben Beat” and produces scorched dance-punk on “Crystal Breath.” Her adventurousness is grounded by candor. She wrote these eclectic songs between 2011 and 2022, years she spent home in Dayton caring for her ailing parents, who both passed shortly before the pandemic, and the album’s bittersweet tenor mixes grief, beauty, regret, and release, sometimes all at once. She repeatedly sings of wanting to duck out of her life to start over, longing for real change. “Show me what’s not possible/And I’ll come running,” Deal sings on the expressive “Come Running,” where she plays every unhurried instrument.

On “Coast,” Deal pairs blunt, end-of-the-road storytelling with a breezy melange of trombone and trumpet, creating the picture of the tropical trickster grinning through grim times. “Clearly, all of my life I’ve been foolish,” she sings over its midtempo sunshine pop, her rasp buoyed by the ornate arrangement. “Tried to hit hard, but I blew it/But it don’t even matter/It’s just human to want a way out/It’s human to wanna win.” What might otherwise sound like a harsh reflection becomes amiable wisdom in Deal’s delivery, horns like life savers bobbing among her mellow melodies. Deal has said that the song was inspired by her experience of attempting to dry out in Nantucket in the late ’90s—years when the Breeders’ momentum from the platinum-selling Last Splash was derailed by addiction struggles. Deal watched young townies surf, thinking, How nice to be a person doing things outside, in daylight! Her frank storytelling makes “Coast” the most vivid song on Nobody Loves You More, like the account of a beachside outlaw whose levity is its own triumph.

The best moments are when Deal slows her pace and stretches out like a daydream, recalling, more than any of her other bands, her sublime cover of Chris Bell’s “You And Your Sister” with This Mortal Coil in 1991. The stirring “Are You Mine?” is a ’50s-style doo-wop slow-burner inspired by a time that Deal’s mother, who was struggling with Alzheimer’s, passed her in the hall: Her query—“Are you mine? Are you my baby?”—became the song’s hazy hook, the pedal steel a welling tear. The languid chug of “Wish I Was” feels of a piece, like a lost psych-pop Love tune unapologetically yearning to get back to youth. These atmospheric songs hinge on tiny details: the rise of a Beatles-esque guitar solo, the heavenly harmonies pouring down, the sudden admission that “I may find deep regret waiting for me in the end.” Deal croons “Summerland” like an alt-rock Sinatra or post-grunge Gershwin filled with total wonder: “I hear music blowin’ in the breeze.”

The Rat Pack style of “Summerland” and the easy groove of “Coast” carry the reassuring memory of older generations; knowing that Deal penned these tunes while losing her parents, you understand why she would want to sink into such palliative spaces. The elegiac title track, too, feels like a sweeping ode to the way that, even when we are adrift in life, love becomes an anchor. Like most of Nobody Loves You More, its statement of abiding adoration also marks Deal’s final collaboration with her late friend Steve Albini, with whom she once worked on the eternal, howling high harmonies of “Where Is My Mind” and the Breeders’ sensory masterpiece, Pod. It’s endearing, profound even, that Nobody Loves You More found these no-frills indie legends tracking an orchestra and a marching band together at Electrical Audio—a radical left turn expanding our images of two artists better known for efficiency. What could be cooler?

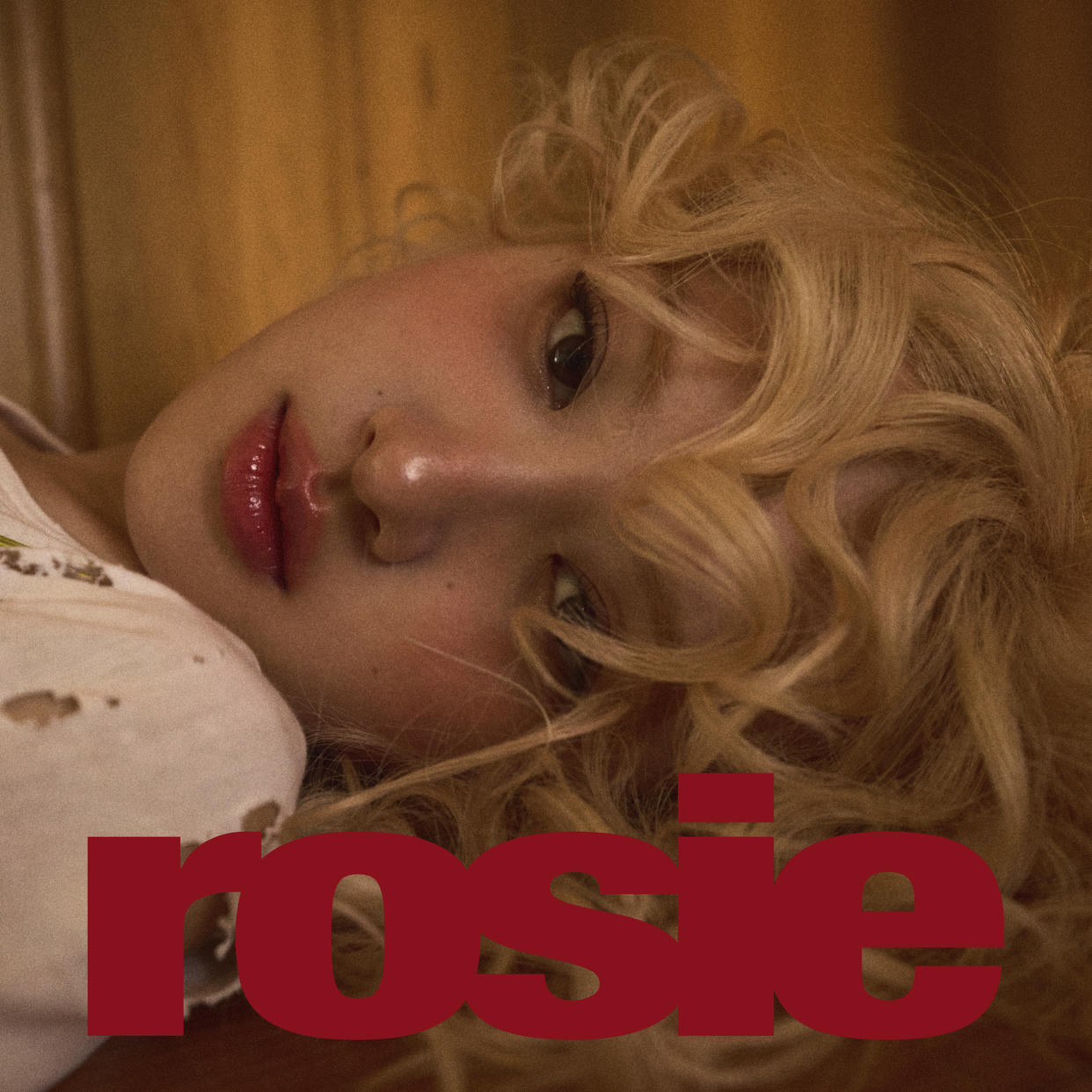

Who is Rosé, outside of being the main vocalist of record-smashing K-pop girl group BLACKPINK? When she announced rosie, her solo debut solo with Atlantic, Rosé hinted that listeners would get a new perspective on her—not just a taste of who she is as an artist, but also a peek into her interior life. “Rosie - is the name I allow my friends and family to call me,” she wrote in an October Instagram post introducing the record. “With this album, I hope you all feel that much closer to me.” But rosie lacks the sense of identity required to tell this story, boasting only dated pop references and a generic feeling of lingering heartache

This question of personal identity is a fraught one in K-pop. So much of the genre is built upon the project of fantasy, where idols are treated like canvases for bigger ideas and themes. The cost of this approach, often, is the idol’s unique self—or, at least, the consumer’s understanding of it. While impressions of the idol’s personality are scattered across behind-the-scenes vlogs, candid livestreams, and maybe a personal Instagram account (if their company allows it), this human touch is rarely expressed in the music itself. Though let’s be clear: In K-pop, this quality is not commonly a point of contention, or even a factor that makes or breaks the entertainment value.

The lack of personal identity doesn’t always serve idols who branch out solo—after all, many are trained to perform as part of a whole. Soridata, a site that aggregates data for Korean music, reports that female soloists have received only 9.3 percent of music-show awards since 2007. (Many wins can be attributed to singer-songwriter IU, who has recorded solo since 2008.) That hasn’t stopped BLACKPINK’s members from trying, however. In late 2023, Jennie, Jisoo, Lisa, and Rosé chose not to renew their individual contracts with YG Entertainment (though they did renew their contract for group activities as BLACKPINK), opting to move away from the agency for their solo ventures. By the time the news reached the public, Jennie had established her label, Oddatelier, followed shortly by Lisa’s company, LLOUD, and the announcement of their respective record deals.

For her part, Rosé broke out with rosie’s lead single “APT.,” an infectious pop-rock collaboration with Bruno Mars. Despite the track’s simple structure and premise, which riffs on a Korean drinking game, Rosé lets loose. Her vocals soar over fuzzy synths and catchy percussion, narrating the highs, lows, and inherent humor of a night spent in a drunken stupor. Crucially, the song showcases her most valuable instrument: her voice, a malleable asset that can chant, shout, harmonize, and sing without losing the timbre that makes it recognizable in any language.

The rest of rosie doesn’t capture the same spark: Its dominant narrative of heartbreak is more preoccupied with trying on different styles for size. Third single “Toxic Till the End” is an almost clinical synth-pop track that kicks off an energetic, genre-confused four-song run that represents the album’s most interesting arc. There’s a booming bass synth reminiscent of Taylor Swift’s 1989, a motif that could have boosted the record’s emotional peaks if it appeared more than once or twice. The lyrics detail a bad relationship in which both parties are complicit, building to a cathartic bridge: “I can forgive you for a lot of things/For not giving me back my Tiffany rings,” Rosé sings. “I’ll never forgive you for one thing, my dear/You wasted my prettiest years.” Her rage is a welcome departure on an album that otherwise mostly expresses longing or regret.

Musically, rosie plants itself in the shadow of pop’s recent past, falling somewhere between Sam Smith’s In the Lonely Hour and Halsey’s Badlands. There’s “Drinks or Coffee,” an attempt at a sultry, R&B-inflected pop hit torn between naughty and nice; there’s the punny red-flag anthem “Gameboy,” which layers an acoustic guitar loop over a nonspecific jungle track; there’s “Two Years,” another take on 1989-era Swift. The final third of the tracklist meets Rosé’s power-ballad vocals with bland coffeehouse sounds, like the pretty fingerpicked guitar on “Not the Same” or the muffled piano on “Call It the End.”

Even with the support of a major label, a star-studded committee of songwriters and producers, and Rosé’s eight years of experience in BLACKPINK, rosie offers nothing revealing or exciting. Its writing pales in comparison to the canon of great breakup albums, with lines like, “In the desert of us, all our tears turned to dust/Now the roses don’t grow here.” Rosé’s recounting of the undoing of this relationship feels distant: There’s a “we,” an “us,” and an “I” accompanied by a “you,” but no real assertion of her own point of view, whether in the context of her persona Rosé or as 27-year-old Rosie. Compare this to her work with BLACKPINK; on “Lovesick Girls,” she sang, between Korean and English: “Love is slippin’ and fallin’/Love is killin’ your darlin’,” balancing the experience of joy and pain. In trying to live up to the “personal album” trope, rosie opts to explore rather than define, and the emotional grooves are polished smooth. Whether you’re a new fan or a devoted Blink (as BLACKPINK fans are known), you’re likely to feel left cold.